Category: Housing, Justice, Listening Sessions, Personal Stories, Poverty News & Policy Updates, The Safety Net, Wealth Building, Work

August 09th, 2022

Liliana Madrigal is an Educator and Conceptual Artist living in Clovis, CA. Author’s note: From August 3-August 26 farmworkers will march 335 miles – from Delano, CA to the State Capitol in Sacramento – for the right to vote for a union free from intimidation and threats. Sign up to join this historic march for one or more days!

This month, as farmworkers march 335 miles to Sacramento for the right to vote for a union free from intimidation, it is worth considering how society treats these essential workers like ghosts: They move from one farm camp to another – following the fruit seasons – whether picking, planting, or trimming trees. We see movement, we see traffic, we see the stores full of produce that comes from our valleys. We see our plates full of food. But we don’t see the people who make all of this possible – their humanity, the condition of their lives.

I have experienced this life personally. In 2001, I migrated with my parents and five siblings from Michoacán, Mexico to Fresno, California. We are a family of farmers going back generations, so my dad continued the only profession we had ever known.

We lived in a small, two-bedroom apartment for many years, paying high rent. It was crowded, and the landlord didn’t do much to maintain the property. My mom got a job as a housekeeper at a hotel where she worked long hours at minimum wage. I was too young to understand what was going on or how we were living. I was happy, my family was together, and we were healthy – that was what we valued the most.

But years passed and I saw a cycle repeat itself: Migrant families working all the time to barely make ends meet. I had had enough – I decided I would be a first generation college graduate. I wanted a profession that would allow me to help students like myself who had to learn English and also had responsibilities like translating for their parents. That has been my journey ever since.

In 2009, I began my studies at Fresno State and got involved doing service work in non-profit organizations, like Education Leadership Foundation and the Binational Center for the Development of Oaxacan Indigenous Communities (CBDIO). Through my volunteer work I gained a deeper understanding of the many struggles migrant farmworkers continue to face – from poverty wages, to trafficking, to a lack of access to healthcare, harassment and abuse in the fields, and more. Too many people think that the law and unions now protect these workers who are at the very foundation of our life and economy. With this in mind, through my work as an artist, I wanted to make visible the dignity and humanity of the people who work our land and play such an integral role in making California’s economy the fifth largest in the world.

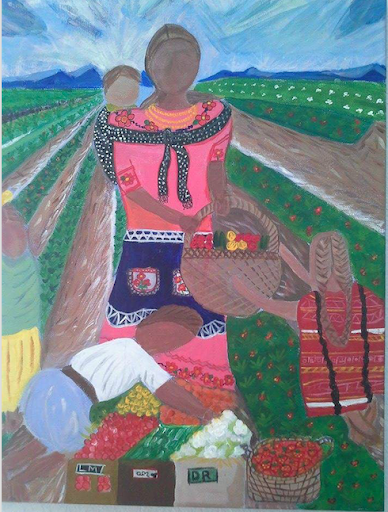

In 2015, as a contribution to a fundraiser for CBDIO, I painted “Vendedores de vida” (which in English means “Vendors of Life).” The piece is influenced by Diego Rivera’s “Vendedores de flores.” I was inspired by thousands of migrant workers – mostly Mixtecos, Triquis, and Zapotecos – who continue to work the fields in California, Oregon, Washington, and sometimes the Valley of San Quintin, Baja California, Mexico. Many are women and children, something most in our media fail to portray, focusing instead on men in the fields.

My painting seeks to exhibit this reality as well as criticize it. As consumers, when we go to supermarkets, we usually do not think about the farmworker. We do not think of small or delicate hands of women and children. My painting is composed of a family: the mother carrying her baby on her back; two girls, one on each side of their mother; and her son standing next to boxes of cucumbers, chili peppers, tomatoes and other products. Their bodies are abstract and faceless because they are not treated by society as fully human. They have no right to a better future, they cannot breathe pesticide-free air, they cannot eat well because they aren’t paid enough.

The mother and a girl wear traditional indigenous clothing, including a red huipil and colorful flower fabrics. The mountains in the background are characteristic of the many valleys where they work. The long diagonal grooves have a focal point at the baby’s face, which represents a better future. The family is barefoot – like Augustus in the famous marble statue Augusto de Prima Porta – because, traditionally, gods were portrayed as barefoot and so it is associated with divinity. The family is directly connected to mother earth, and it is the earth – as well as the labor of the farmworkers – that give us all life.

We can write and talk about the struggles of farmworkers, with pesticides, sexual harassment, child labor, and more – and we should. But art can give light, open hearts, and plant seeds for change.