Category: Listening Sessions, Personal Stories, Poverty News & Policy Updates, The Safety Net

January 02nd, 2024

Kimberly Wear is the assistant editor of the North Coast Journal.

This article originally appeared in the North Coast Journal.

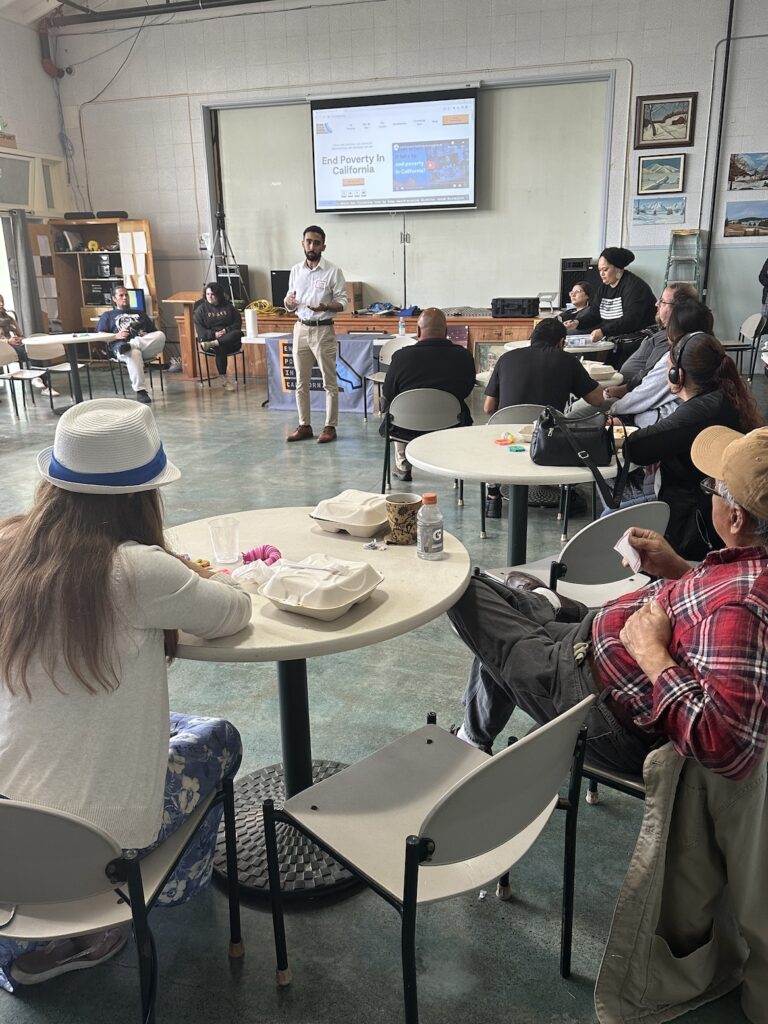

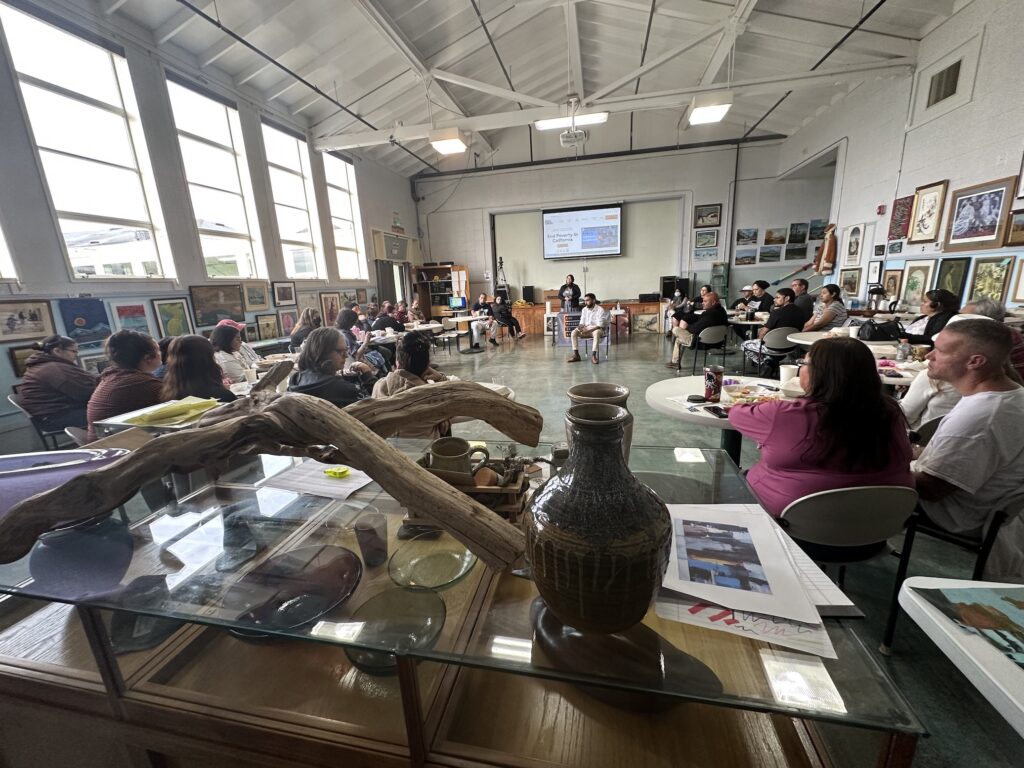

On a recent Friday night, about two dozen people sat around small tables in a room at Eureka’s Jefferson Center, talking about the realities of living on the financial brink.

Each had their own story to tell, but common threads in the obstacles they face trying to not just make ends meet, but forge a path forward were woven throughout the discussion — from a lack of affordable housing and access to medical care to difficulties navigating assistance programs and seemingly impossible choices between whether to buy food or medicine.

“It’s just so frustrating, because you can’t get ahead,” one said.

While most of those attending were strangers to each other, they were brought together as part of a “listening session” organized by End Poverty in California (EPIC), a nonprofit that has been crisscrossing the state for the last year to hear from people with first-hand experience traversing the landscape of living in poverty.

EPIC’s concept behind the forums is simple: “The people closest to the problem are closest to the solution.”

At the center of a semi-circle formed by tables during the recent Humboldt County stop sat EPIC President Devon Gray in tan slacks with the sleeves of his white dress shirt rolled up. In a calming tone he explained that the stories being shared in the room would help inform the policy changes EPIC will lobby for at the state Capitol.

As each person spoke, Gray turned to face them, often jotting notes in a charcoal-colored notebook.

One woman described how she was “ecstatic” to land a job making $17 an hour but her hopes for a “second chance in life” came crashing down when she lost state medical benefits as a result of working extra shifts. That meant she was cut off from therapy sessions that had helped her stay sober for more than a year and put a medication she needs out of financial reach, she said, all for making “a few hundred extra dollars.”

In addition, the woman said, she not only lost access to CalFresh SNAP benefits, a state nutrition program formerly known as food stamps, that helped stretch her income, but was told she owed money back.

“Just because I was given the opportunity to better my life, they are taking that away from me,” she said.

Over and over, similar stories unfolded throughout the evening.

A young pregnant woman who recently moved to the area spoke about trying for weeks to access temporary benefits as she searched for a job.

“I felt like I had to beg for Medi-Cal just to see my prenatal doctors,” she said.

Another participant said he faced a similar wait while trying to reapply for benefits after being repeatedly told he needed to provide more information.

“It was just months of not having food. I had to go to food banks,” he said. “It was hard.”

One person said what really bothered them was how assistance programs only looked at a person’s gross income.

“I’m not bringing home my gross income,” they said, adding there is “no ability to jump classes” with the way the system operates.

“Being able to get out of intergenerational poverty is unheard of in Humboldt County,” they said.

“The government does a really good job of creating barriers,” Gray noted.

One young woman broke down as she described how it was “really scary” to watch her grandparents have to choose between paying bills and buying medicine after working hard their entire lives.

“My grandmother almost had to go to the hospital because her diabetes was out of control because she couldn’t afford insulin,” the woman said, adding her grandparents are considering whether to sell their house.

“I’m so sorry,” Gray told her.

While an estimated 12 percent of Californians live in poverty, according to U.S. Census data, Humboldt County’s numbers are bleaker, with an estimated 20 percent of households living below the federal poverty line — $30,000 in annual income for a household of four — while the county’s median household income comes in at $53,000 compared to $84,000 statewide.

In 2022, an average of 17,500 Humboldt County households, encompassing 27,000 individuals, received CalFresh benefits, or one in five residents, according to the California Department of Socials Services. To qualify, a family of four has to make less than $39,000 before taxes while a single individual’s income threshold is just under $19,000.

According to the nonprofit California Healthcare Foundation, 64,901 people in Humboldt County were enrolled in Medi-Cal in July of 2023, or 47.4 percent of the population. Statewide, 39.8 percent of Californians are enrolled.

In a later interview with the Journal, Gray said one of the reasons the listening sessions are so important is that poverty manifests itself in different ways depending on where people live.

On a broad scale, he said, EPIC — formed last year by Michael Tubbs, a former Stockton mayor who made national headlines by starting a guaranteed income pilot program during his tenure — works to advocate for policies that enhance economic mobility in the state, addressing everything from housing issues and workers’ rights to entrepreneurial support and reforms of the criminal justice system and safety net programs.

While the nonprofit’s focus is primarily directed at the Legislature, the group engages with local government as well, Gray said.

Then there’s what he described as EPIC’s “storytelling work” though the listening sessions, “with the idea that the narratives around poverty are often the biggest impediments to actual policy change.” The most problematic false narrative, Gray said, is the idea that poverty is somehow an individual failing, “that people are poor because they choose to be or because they are lazy or otherwise somehow morally flawed or irresponsible.”

From EPIC’s perspective, he said, the more accurate narrative about poverty is “one that focuses on policy choices and systems that set people up for failure.”

Before each visit, Gray said, EPIC reaches out to community organizations that work with local residents experiencing poverty, which in turn assist the nonprofit in connecting with community members to participate in the listening sessions.

On the Humboldt tour, those included the Jefferson Center, Food for People, the McKinleyville Family Resource Center and Project Rebound at Cal Poly Humboldt, which helps enroll and support formerly incarcerated students.

“We made a lot of great partnerships that I think are going to be long lasting,” Gray said.

He also noted the McKinleyville Family Resource Center was the only rural organization in California to be awarded one of seven state grants to initiate a guaranteed income pilot program, akin to Tubbs’ efforts in Stockton, which locally will provide 150 pregnant women who meet certain eligibility requirements $920 a month for 18 months — no strings attached.

Enrollment is slated to begin in December.

Gray said many of the stories he heard in Humboldt are echoed by people living in poverty across the state, but other challenges are unique to the rural nature of the North Coast. He pointed to the need to travel long distances for medical care due to a lack of doctors and dentists, and spotty internet service that makes applying for safety net services even more difficult.

“So the reason why we tour the state, why we go everywhere from Crescent City down to San Diego and everywhere in between, is because we think it’s really important to ensure the stories that really capture the very diverse experiences of Californians living in poverty are reflected in the broader narrative,” Gray said. “And also that the policies that we are pushing for are actually grounded in people’s experiences, and not just coming from our presumptions or from think tanks from people who aren’t connected to what people are going through on a day-to-day basis.”

And, he said, EPIC wants to make sure “that when we are in Sacramento and working with legislators and people in the governor’s office, what we are saying is actually grounded in the reality of people’s experiences … and that the stories we tell are authentic ones.”

One of the universal issues that comes up no matter where EPIC goes is the conversation around accessing benefits, he said.

“The safety net has to be our North Star on the policies that we are pushing for because we have the money … the infrastructure already exists, but we create so many barriers to entry and many times these barriers are because of the bad narratives that we talked about,” Gray said. “The reason why we have work requirements and all the hoops that people have to jump through is because there is this inherent distrust of people living in poverty. And that leads to us structuring these programs to be focused more on fraud prevention than services delivery.”

The benefit cliff issue, in particular, he said, “is so evil in so many ways” because people honestly reporting their income are being punished by having their benefits taken away for making a little extra money.

“They try to play by the rules and then they just end up further behind than when they started,” he said.

EPIC is currently in talks with what Gray would only describe as a large California county on a pilot program that would allow recipients to stay on benefit programs longer and taper down the assistance over time.

Gray said one of the biggest takeaways from EPIC’s tour through the northern reaches of the state, which included stops in Redding, Weaverville and Crescent City, as well as the one in Eureka, was that people feel there is a real disconnect in Sacramento and a “tendency to fall into one-size-fits-all policy making” on issues concerning the economy and people’s economic mobility.

“But in a state as diverse as ours, where people really live very different lives depending on where they live … that one-size-fits-all approach really falls short,” he said.

Back in Humboldt County, Gray told the group that one of the lessons EPIC learned during these listening sessions is that “rural poverty looks very different.”

Several people brought up impacts from the region’s geographical isolation, including how gas is more expensive than other areas of the state — AAA lists Humboldt’s average price on Monday at 10 cents a gallon more than the state as a whole — and how wages are lower but housing prices have skyrocketed in recent years, putting the dream of ownership out of the reach of many.

According to Realtor.com, the average home sold for $368,500 in November of 2020 before reaching a high of $555,500 in September of 2021. Last month, the median sold price was $468,000.

Meanwhile, one person said, rents are increasing, leaving people in what they described as a “vicious cycle” of trying to come up with another round of deposits while searching for a less expensive place to live in a competitive market.

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), no more than 30 percent of a household’s income should go toward paying rent. For a family of four making Humboldt’s median income of $53,000 that translates to $1,325 a month in an area where a two-bedroom apartment averages around $1,200 to $1,500, according to online rental sites Zillow and Zumper. In the case of a family living at the poverty level, their rent would need to be $750 or less to meet HUD’s 30-percent rule.

Similarly, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Living Wage Calculator estimates a family of four in Humboldt County with two working parents would need both of them to earn $26 an hour to meet their basic needs, and that’s assuming a housing cost of $13,699 a year, or $1,140 per month.

“It’s so isolated here,” another speaker said. “You don’t have a lot of options.”

When Gray asked those gathered whether they felt elected officials in Sacramento heard them, aside from their own representatives, a susurrus of responses echoed across the room.

“People don’t even know Humboldt is in California,” one person answered.

As the night wrapped up, Gray told the group that EPIC would be staying in touch with them and the stories they shared would not disappear, but will go toward combating the false narratives surrounding poverty while also helping guide policy changes that the nonprofit will be pushing in the Capitol.

“Thank you for your candor and your wisdom and insight,” he said.